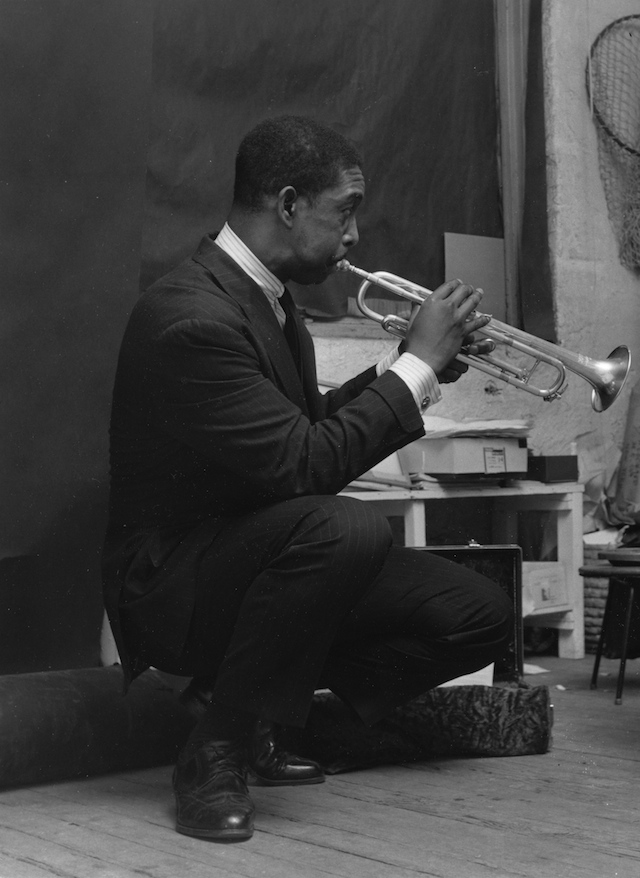

Kenny Dorham possessed a rare, soft and vulnerable sound that is soothing and instantly identifiable. Eschewing the typical trumpeter’s showmanship and flashiness, Dorham instead relied on his economical melodic logic in constructing poetic, lyrical improvisations with meaningful beginnings, middles, and ends.

His technique is also unique: Dorham chose to attack notes with his tongue, where most of his bebop contemporaries would slur for a more continuous flow. His clearly articulated lines had a singular running quality to them that fleetly pushed ahead of the time.

At mid-tempos, Dorham distinctly articulated an exaggerated staccato swing feel, greatly contrasting his double-timed legato phrases. On ballads, Dorham would not stray far from the melody, his minimalist approach exposing the innate beauty of each melody he touched. His idiosyncratic use of grace notes, varied attacks on single notes, such as scooping underneath or bending above the pitch, and stuttering repetitions of notes were some of the personal nuances that decorated his deceptively complex improvisations.

Paradoxically, the fact that Dorham was nearly always the first-call replacement in all-star groups, which should be a testament to his talents, has led to a perception that he was a second-tier trumpeter, when nothing is farther from the truth. Dorham replaced Fats Navarro in Billy Eckstine’s band in 1946, Miles Davis in Charlie Parker’s quintet in 1949, and Clifford Brown in Art Blakey and Horace Silver’s Jazz Messengers in 1954 and again in the Max Roach group in 1956.

Dorham was constantly overshadowed by more obviously brilliant and original voices during his lifetime. He had the misfortune to play beneath the shadows cast by Gillespie, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown and Miles Davis. Only in the 18 years since his death has a fuller and wider appreciation of KD’s talent developed. There is now a “school” of Dorham trumpet playing.